Honors Chemistry Notes

An unofficial collection of chemistry notes

These are quick-reference notes for Honors Chemistry. They are organized into sections for convenience, and are arranged in alphabetical order (work-in-progress).

Table of Contents

- Required Formulas

- Required Symbols

- Atomic Models

- Subatomic Particles

- Flame Tests

- Acids and Bases

- States of Matter

- Electron Configuration

- Electron Diagonal Rule

- Orbital Notation

- Radioactivity

- Nuclear Equations

- Calculating Half Life

- Ionization Energy

- Electronegativity

- Electron Affinity

- Electrical Conductors and Insulators

- History of the Periodic Table

- Chemical Polarity

- VSEPR Theory

- Key Features of Hybridization

- Chemical Reactions And Equations

- Stoichiometry

Required Formulas

Not finished yet, sorry!

Required Symbols

- $\rho$ - stands for density, measured in mass/volume

Atomic Models

- The definition of an atom has developed throughout history

- Our modern understanding of atoms is built on the theories of previous scientists

- Each had a different definition of an atom (could be same or different from our understanding today)

Democritus

Indivisible units of matter

John Dalton

The smallest units of matter that react chemically and have definite and characteristic mass

J. J. Thompson

"Plum-pudding model" - A positively-charged center with negatively-charged electrons around it.

Ernest Rutherford

"Nuclear Model" - Most of the atom is empty space, but most of its mass is concentrated in the nucleus.

Niels Bohr

Electrons orbit around the nucleus in discrete orbitals (shells) based on their energy level.

Erwin Schrödinger

"Electron Cloud" - Electrons are located in arbitrary locations around the nucleus and and orbit in complex higher-dimensional non-Euclidean orbit.

"Electron Cloud" - Electrons are located in arbitrary locations around the nucleus and and orbit in complex higher-dimensional non-Euclidean orbit.

Subatomic Particles

Nucleus

- The combined mass of the nucleons is called the atomic mass and is measured in atomic mass units (AMU)

Protons

- The number of protons is the atomic number

Neutrons

Electrons

- In uncharged atoms, the number of electrons is equal to the atomic number

- In ions, the number of electrons is equal to the atomic number, minus the charge (e.g. a -2 charge with atomic number 5 has 5-(-2)=7 electrons)

Isotopes

-

To calculate the relative abundance of an isotope, use this formula:

$$ \begin{cases} A = I_1x+I_2y \ x+y=1 \end{cases} $$

Where $x$ and $y$ represent the relative abundance of each isotope, $I_1$ and $I_2$ are the given isotopes of an element, and $A$ is the actual atomic mass

- Example: The element Spidermanium is composed of two isotopes: $^{46}Sd$, which has an actual mass of 45.84 amu, and $^{43}Sd$, which has an acutal mass of 43.25 amu. If the atomic mass of Spidermanium is 44.25 amu, determine the percent abundance of the two isotopes.

- Let $x$ and $y$ = % abundance:

$$ \begin{cases} A = 45.84x+43.25y \ A = 44.25 \ x+y=1 \end{cases} $$

$$ x=\left(\frac{100}{259}\right), y=\left(1-\frac{100}{259}\right) \ $$

$$ x=38.6%, y=61.4% $$

Info to memorize

- Ions have more or less electrons than protons

- Uncharged atoms have the same number of electrons and protons

- Isotopes have a different number of protons and neutrons

- Atoms with the same number of electrons are isoelectronic

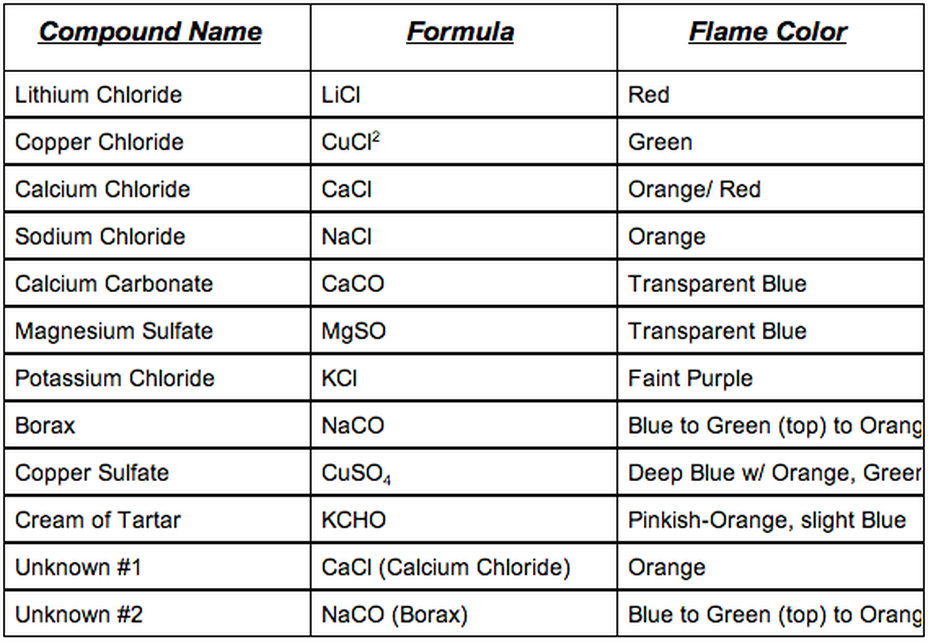

Flame Tests

Theoretical Knowledge

- When heat is applied to atoms, electrons gain energy

- The electrons are excited (rise to high energy levels), then fall to lower levels by releasing their energy

- Example: Neon (Ne) releases an electron when excited

$$ \textit{Ne} \rightarrow \textit{Ne}^++e^- $$

-

The energy released is in the form of visible light

-

We can detect the element based on the light emitted

Practical Knowledge

-

The most common flame tests:

Acids and Bases

Identifying Acids

Identifying Bases

- Has an hydroxide ion ($\text{OH}^-$)

States of Matter

- The main states of matter:

- Solid

- Liquid

- Gas

| Appearance | Change of State | Intermolecular Forces (IMF) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid | Has unique shape independent of container, and has definite volume | Melting, Freezing; Sublimation, Deposition | Strong |

| Liquid | Takes shape of container, but has definite volume | Vaporization, Melting | Strong |

| Gas | Has no defined volume nor shape; can be colorless | Vaporization, Condensation; Sublimation, Deposition | Weak |

- Changes of State occur when an element gains or loses heat energy

Electron Configuration

- Electron configuration is how the electrons are arranged within an atom

- Electron configuration is notated based on these rules:

- Electrons orbit in specific energy levels (also called "shells") around the nucleus

- Each shell can contain multiple sub-energy levels

- The number of the shell determines how many energy levels it has

- E.g. shell 1 has only 1 energy level, shell 2 has 2, etc.

- The sub-energy levels are called the $s$, $p$, $d$ and $f$ sub-energy levels:

$$ 1s^2 $$

$$ 2s^2\ 2p^6 $$

$$ 3s^2\ 3p^6\ 3d^{10} $$

$$ 4s^2\ 4p^6\ 4d^{10}\ 4f^{14} $$

$$ 5s^2\ 5p^6\ 5d^{10}\ 5f^{14} $$

$$ 6s^2\ 6p^6\ 6d^{10}\ 6f^{14} $$

$$ 7s^2\ 7p^6\ 7d^{10}\ 7f^{14} $$

$$ \dots $$

- Each sub-energy level has 4 more electrons than the previous level

- E.g. $s=2$, $p=s+4\ (6)$, $d=p+4\ (10)$

- The superscripts ($2$ in $s^2$) indicate the maximum number of electrons in the sub-energy level

- The electronic configuration of Iron ($_{26}\text{Fe}$) is $1s^2 2s^2 2p^6 3s^2 3p^6 4s^2 3d^6$

- This means that its electrons are arranged as 2. 8. 14. 2.

Note that the $4s^{(2)}$ shell is usually written before the $3d^{(10)}$ shell

Electron Diagonal Rule

- The electron diagonal rule shows the location of electrons

- It is a basic rule for writing the electronic configuration

- It states that:

Electron configuration is written from top to bottom and diagonal right to diagonal left.

Aufbau Principle

Start with lowest energy level first when writing out the electronic configuration

Pauli Exclusion Principle

There can only be 2 electrons in each orbital with opposite spin

Hund's Rule

Every orbital in a sub-energy-level is singly occupied before any orbital before any orbital is doubly occupied

Orbital Rules

| Subenergy Level | Max no. orbitals | Max n. of electrons |

|---|---|---|

| $s$ | $\bigcirc$ | 2 |

| $p$ | $\bigcirc$ $\bigcirc$ $\bigcirc$ | 6 |

| $d$ | $\bigcirc$ $\bigcirc$ $\bigcirc$ $\bigcirc$ $\bigcirc$ | 10 |

| $f$ | $\bigcirc$ $\bigcirc$ $\bigcirc$ $\bigcirc$ $\bigcirc$ $\bigcirc$ $\bigcirc$ | 14 |

Orbital Notation

- Orbital notation is just another way of writing electron configuration

- We represent each subshell as a circle $\bigcirc$ or square $\square$, with electrons represented as arrows $\uparrow$ $\downarrow$

- We use an up arrow $\uparrow$ for clockwise spin and a down arrow $\downarrow$ for counterclockwise spin

- For instance, these are the electron configurations, written in orbital notation, of nitrogen, oxygen, flourine and neon:

Radioactivity

Nuclear Equations

Calculating Half Life

- Each radioisotope has a unique half-life, which is defined by this formula:

$$ M=P\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{t/d} \ $$

Where:

- $d$ is the half-life,

- $t$ is the number of years,

- $P$ is the original amount,

- $M$ is the final amount

Ionization Energy

-

Ionization Energy is the energy required to remove the outermost electron(s), resulting in a positive ion (cation)

-

In general, elements with more outer shell electrons have higher ionization energy

-

In the Periodic Table, there are 2 major trends for ionization energy:

-

Ionization Energy increases from left to right

-

This is because the number of protons are increasing towards the right of the Periodic Table

-

Ionization Energy decreases from top to down

-

This is because the number of energy levels increases as you go down the Periodic Table

-

8 outermost electrons, also called an octet, is a very stable configuration. This results in a very high ionization energy (effectively impossible to achieve in real life). So, we can consider 8 outer shell electrons as unmovable.

Electronegativity

-

Electronegativity is a measure of the attractiveness of an atom for an electron of another atom

-

Electronegativity determines whether a compound is ionic or covalent

-

Some compounds are highly electronegative, such as oxygen, fluorine, and chlorine

-

Other compounds are highly electropositive (the opposite of electronegative), such as sodium, potassium and cesium

Electron Affinity

-

Electron Affinity is the energy change that occurs when an atom gains an electron and becomes a negative ion (anion)

-

An atom with a high electron affinity is highly attracted to other electrons, while atoms with low electron affinity (e.g. noble gases) are only slightly attracted to other electrons

-

In the Periodic Table, there are 2 major trends for electron affinity:

-

Electron affinity increases from left to right

-

This is because the electronegativity of atoms increases towards the right of the Periodic Table

-

Electron affinity decreases from top to down

-

This is because the electronegativity of atoms decreases as you go down the periodic table

-

Electrical Conductors and Insulators

-

Electrical conductivity is only displayed in substances that both have ions and are within a state that allows their ions to freely move (such as an aqueous solution or in liquid state, or are metallically bonded)

-

Three main types of solutions can conduct electricity (making them electrolytes) - acids (e.g. ascorbic acid), bases (e.g. aqueous sodium bicarbonate), and salts (e.g. aqueous sodium chloride)

-

In addition, pure metals can conduct electricity as metal atoms bond with metallic bonds, which allow their electrons to freely move in a "sea of electrons"

-

Covalent compounds (made of non-metals) cannot be electrolytes, because they do not have ions

History of the Periodic Table

-

Dmitri Mendeleev was the first to propose a table of the elements that was based on periodic (meaning recurring) trends

-

Henry Moseley was the first to organize the elements in order of increasing atomic number, not atomic mass

-

More notes coming...

Chemical Polarity

-

Polarity occurs where two different atoms in the same molecule have different electronegativity (attraction or "pull" on other atoms' electrons towards itself)

-

As a result, the electrons in the bond are not shared equally by the two atoms

-

This causes an asymmetrical (polar) electric field

-

Therefore, the atoms share a polar bond, where one atom has more electrons than the other

-

If the atoms share a nonpolar bond, then the resulting compound will display symmetry, and vice-versa if the compound is polar

-

Only covalent compounds or covalent bonds can be described as polar or nonpolar

Polarity Calculations

-

We can determine the polarity of a bond by finding the difference between the electronegativites of each atom within the bond

-

A nonpolar bond has two atoms of equal electronegativity, and thus the difference between the electronegativites of the two atoms is 0

-

A polar bond has two atoms of unequal electronegativity, and the difference between the electronegativites of the two atoms is the polarity of the compound (how polar it is, or essentially how unbalanced the relative charges are)

Effects of Polarity

Polar substances are affected by an electric field

Covalent Bonding

To be finished...

Valency

- Valency is the number of bonds that an element tends to form

- Noble gases have a valency of 0, as they do not typically form bonds

Lewis Structures

- Lewis Structures are used to notate the structural formula of a covalent compound, including:

- Whether the compound is symmetrical or non-symmetrical (which tells us if it's polar or non-polar)

- Whether the bonds formed are single, double or triple bonds

- The valence electrons of each compound

- More notes coming...

VSEPR Theory

The VSEPR Model

-

Valence-shell electron-pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory is used to find the geometry that minimizes the repulsion between electrons in the valence shell of that atom, and in doing so, predict the shapes of molecules

-

To minimise the repulsion between the two groups of electrons, each group of electrons arranges itself into particular geometries

-

These geometries form the basis of the shape of the electron clouds' molecule

-

VSEPR begins by accounting for the total number of valence electrons, present within two molecules, via obtaining the sum of the electrons

-

Then, the least electronegative atom within the molecule is placed within the center of the molecule's structure

-

The terminal atoms (that are more electronegative) are used to complete the dot structure

-

If a molecule includes atoms that are arranged contrary to the octet rule, their lone pairs of electrons can be ignored if they have a neutral formal charge

-

Regions of electron density surrounding the central atom will form into electron clouds

-

Electron clouds are furthest apart (and thus most stable) when pointing in opposite directions, based on the principles of VSEPR, and should thus be arranged in opposite pairs

-

Thus, the geometry of the electron clouds can be seen through their arranged directions and angles

-

If there are no lone pairs of electrons, the molecular geometry will be linear

More notes coming...

VSEPR Molecular Geometries

Symbols:

- A = Central atom,

- X = ligand [atom(s) attached to the central atom],

- E = unshared pair of electrons

| Example | Formula | Molecular Geometry | Bond Angle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 pairs ($sp$) | $\mathrm{CO}$ | $\mathrm{AX}$ | Linear | 180º |

| 2 pairs ($sp$) (continued) | $\mathrm{CO}_2$ | $\mathrm{AX}_2$ | Linear | 180º |

| 3 pairs ($sp^2$) | $\mathrm{BI}_3$ | $\mathrm{AX}_3$ | Trigonal Planar | 120º |

| 3 pairs ($sp^2$) (continued) | $\mathrm{GeF}_2$ | $\mathrm{AX}_2\mathrm{E}$ | Bent / Angular | 120º |

| 4 pairs ($sp^3$) | $\mathrm{CH}_4$ | $\mathrm{AX}_4$ | Tetrahedral | 109.5º |

| 4 pairs ($sp^3$) (continued) | $\mathrm{NH}_3$ | $\mathrm{AX}_3\mathrm{E}$ | Trigonal Pyramidal | 107º |

| 4 pairs ($sp^3$) (continued) | $\mathrm{H}_2\mathrm{O}$ | $\mathrm{AX}_2\mathrm{E}_2$ | Bent / Angular | 105º |

| 4 pairs ($sp^3$) (continued) | $\mathrm{HCl}$ | $\mathrm{AXE}_3$ | Linear | 180° |

| 5 pairs ($sp^3d$) | $\mathrm{PCl}_5$ | $\mathrm{AX}_5$ | Trigonal Bipyramidal | 90º, 120º |

| 5 pairs ($sp^3d$) (continued) | $\mathrm{SF}_4$ | $\mathrm{AX}_4\mathrm{E}$ | Distorted Tetrahedral | |

| 5 pairs ($sp^3d$) (continued) | $\mathrm{BrF}_3$ | $\mathrm{AX}_3\mathrm{E}_2$ | T- Shaped | |

| 5 pairs ($sp^3d$) (continued) | $\mathrm{ICl}_2$ | $\mathrm{AX}_2\mathrm{E}_3$ | Linear | 180° |

| 6 pairs ($sp^3d^2$) | $\mathrm{SF}_6$ | $\mathrm{AX}_6$ | Octahedral | 90º |

| 6 pairs ($sp^3d^2$) (continued) | $\mathrm{BrF}_5$ | $\mathrm{AX}_5\mathrm{E}$ | Square Pyramidal | |

| 6 pairs ($sp^3d^2$) (continued) | $\mathrm{ICl}_4^-$ | $\mathrm{AX}_4\mathrm{E}_2$ | Square Planar |

VSEPR Applied Structures

More notes coming...

Hybridisation

-

Hybridisation occurs when one $2s$ and the three $2p$ orbitals are mixed together to make four equivalent $sp^3$ hybrid orbitals

-

Hybridisation can also occur when one $s$ orbital is mixed with another $d$ orbital to give a hybrid orbital

-

Single bonds can only be made with s-orbitals, and all atoms that do not have enough electrons to form a single bond in their s-orbital must form hybridised orbitals

-

There are 6 main categories of hybridization:

-

$sp$ hybridization

-

$sp^2$ hybridization

-

$sp^3$ hybridization

-

$sp^3d$ hybridization

-

$sp^3d^2$ hybridization

-

$sp^3d^3$ hybridization

Note: below section is the hard work of byju, not my work. I will take no credit for this section.

$sp$ Hybridization

sp hybridization is observed when one s and one p orbital in the same main shell of an atom mix to form two new equivalent orbitals. The new orbitals formed are called sp hybridized orbitals. It forms linear molecules with an angle of 180°

- This type of hybridization involves the mixing of one ‘s’ orbital and one ‘p’ orbital of equal energy to give a new hybrid orbital known as a sp hybridized orbital.

- sp hybridization is also called diagonal hybridization.

- Each sp hybridized orbital has an equal amount of s and p character, i.e., 50% s and p character.

Examples of sp Hybridization:

- All compounds of beryllium like BeF2, BeH2, BeCl2

- All compounds of carbon-containing triple Bond like C2H2.

$sp^2$ Hybridization

sp2 hybridization is observed when one s and two p orbitals of the same shell of an atom mix to form 3 equivalent orbital. The new orbitals formed are called sp2 hybrid orbitals.

- hy2 bridization is also called trigonal hybridization.

- It involves mixing of one ‘s’ orbital and two ‘p’ orbital’s of equal energy to give a new hybrid orbital known as sp2.

- A mixture of s and p orbital formed in trigonal symmetry and is maintained at 1200.

- All the three hybrid orbitals remain in one plane and make an angle of 120° with one another. Each of the hybrid orbitals formed has 33.33% s character and 66.66% ‘p’ character.

- The molecules in which the central atom is linked to 3 atoms and is sp2 hybridized have a triangular planar shape.

Examples of sp2 Hybridization

- All the compounds of Boron i.e. BF3, BH3

- All the compounds of carbon containing a carbon-carbon double bond, Ethylene (C2H4)

$sp^3$ Hybridization

When one ‘s’ orbital and 3 ‘p’ orbitals belonging to the same shell of an atom mix together to form four new equivalent orbital, the type of hybridization is called a tetrahedral hybridization or sp3. The new orbitals formed are called sp3 hybrid orbitals.

- These are directed towards the four corners of a regular tetrahedron and make an angle of 109°28’ with one another.

- The angle between the sp3 hybrid orbitals is 109.280

- Each sp3 hybrid orbital has 25% s character and 75% p character.

- Example of sp3 hybridization: ethane (C2H6), methane.

$sp^3d$ Hybridization

sp3d hybridization involves the mixing of 3p orbitals and 1d orbital to form 5 sp3d hybridized orbitals of equal energy. They have trigonal bipyramidal geometry.

- The mixture of s, p and d orbital forms trigonal bipyramidal symmetry.

- Three hybrid orbitals lie in the horizontal plane inclined at an angle of 120° to each other known as the equatorial orbitals.

- The remaining two orbitals lie in the vertical plane at 90 degrees plane of the equatorial orbitals known as axial orbitals.

- Example: Hybridization in Phosphorus pentachloride (PCl5)

$sp^3d^2$ Hybridization

- Sp3d2 hybridization has 1s, 3p and 2d orbitals, that undergo intermixing to form 6 identical sp3d2 hybrid orbitals.

- These 6 orbitals are directed towards the corners of an octahedron.

- They are inclined at an angle of 90 degrees to one another.

Key Features of Hybridization

- Atomic orbitals with equal energies undergo hybridization.

- The number of hybrid orbitals formed is equal to the number of atomic orbitals mixing.

- It is not necessary that all the half-filled orbitals must participate in hybridization. Even completely filled orbitals with slightly different energies can also participate.

- Hybridization happens only during the bond formation and not in an isolated gaseous atom.

- The shape of the molecule can be predicted if hybridization of the molecule is known.

- The bigger lobe of the hybrid orbital always has a positive sign, while the smaller lobe on the opposite side has a negative sign.

Chemical Reactions And Equations

Types of Chemical Reactions

- The main types of chemical reaction are: decomposition reactions, double replacement reactions, single replacement reactions, synthesis reactions, combustion reactions, and redox reactions

-

A decomposition reaction results in the breakdown of the individual chemical components within the reactants

-

Such a reaction usually takes the form $AB \rightarrow A + B$

-

For instance: $2H_2O_2 \rightarrow O_2 + 2H_2O$

-

A catalyst can be used to speed up a decomposition reaction, but it is not part of the equation (we usually write those on top of the arrow instead)

-

A double replacement reaction results in the formation of two new chemical substances, each composed of the individual chemical components of the reactants

-

Such a reaction usually takes the form $AB + CD \rightarrow AC + BD$

-

For instance: $K_2CrO_4 + 2AgNO_3 \rightarrow 2KNO_3 + Ag_2CrO_4$

-

A combustion reaction results in the formation of a new chemical substance via a reaction with oxygen gas

-

Such a reaction usually takes the form $AB + O_2 \rightarrow AO_2 + BO_2$

-

For instance: $C_2H_6O + 3O_2 \rightarrow 2CO_2 + 3H_2O$

-

A single replacement reaction results in the formation of one new chemical substance, composed of the individual chemical components of the reactant, which is usually one element

-

Such a reaction usually takes the form $A + BC \rightarrow AB + C$

-

Single replacement reactions most frequently produce nonmetal elements in gaseous form

-

For instance: $Zn + HCl \rightarrow ZnCl_2 + H_2$

-

A synthesis reaction results in the formation of a new chemical compound from two or more simpler chemical reactants

-

Such a reaction usually takes the form $A + B \rightarrow AB$

-

For instance: $Fe + S \rightarrow FeS$

-

A combustion reaction is any reaction that has the element oxygen as a reactant

-

For instance: $H_2 + O_2 \rightarrow 2H_2O$

-

A redox reaction results in the loss of electrons for the metal in an ionic compound, and the gain of electrons for the nonmetal in an ionic compound

-

For instance: $\mathrm{Zn^{2+}O^{2-}} + \mathrm{C} \rightarrow \mathrm{Zn} + \mathrm{CO}$

-

All forms of electrolysis and electrochemical reactions are considered redox reactions

-

Balancing Equations

-

Balancing equations are necessary to ensure that the ratios of elements between the reactants and products are equal

-

This means a given number of atoms of one element must stay the same throughout an entire reaction

-

Take, for instance, this balanced reaction: $\mathrm{2KClO_3(s)}\rightarrow \mathrm{2KCl(s)} + \mathrm{3O_2}$

-

We can see that there are 2 potassium atoms on both sides of the equation, 2 chlorine atoms on both side of the equation, and 6 oxygen atoms on both sides of the equation

Stoichiometry

The Concept of Moles

- The mole is a quantity defined as Avogadro's Number, or $6.03 \cdot 10^{23}$

- Another way to understand the mole is simply a specific number with a special name

- For instance, another specific number (12) is also called a special name - a "dozen"

- So we can say there are "a dozen eggs" to mean that there are 12 eggs, or there are "a mole of eggs" to mean that there are 602,210,000,000,000,000,000,000 eggs

- The mole is used to provide a simple measurement to account for the massive numbers of atoms in matter

- It allows us to find the mass of a certain quantity of matter from the number of particle it has, and vice-versa

- For instance, say we want to find the molar mass of carbon dioxide ($\mathrm{CO_2}$)

- We know that Carbon has an atomic mass of 12.01 on the periodic table

- We know that Oxygen has an atomic mass of 16.00 on the periodic table

- So, the total mass in atomic mass units (AMU) would be $12.01 + (2 \cdot 16) = 44.01\ \mathrm{AMU}$

- The mass (in g) of 1 mole of Carbon Dioxide is equal to its atomic mass (in AMU)

- That means the AMU of Carbon Dioxide is 44.01, and 1 mole of Carbon Dioxide has a mass of 44.01g

- In stoichiometry terms, the molar mass of carbon dioxide is 44.01g/mol

Molar Conversions

-

We can also use the mole to convert between mass and moles, using this formula:

$$ n_{mol} = M \cdot \frac{1\ \mathrm{mol}}{m_r} $$

- The number of moles of a certain quantity of a compound is equivalent to the mass of the compound (in grams) divided by the molar mass of the compound

- $n_{mol}$ is the number of moles

- $M$ is the mass, expressed in grams

- $m_r$ is the total atomic mass, expressed in AMU

-

For instance, we have 5.72 grams of $\mathrm{C_6 H_{12} O_6}$ (glucose), and we want to find its number of molecules:

- We know that the mass is 5.72g

- We know that the total atomic mass is $12.0107 \cdot 6 + 1.00794 \cdot 12 + 15.9994 \cdot 6$ which is $180.15588$

- Because we know the atomic mass, we also know that the molar mass is $180.15588\ \mathrm{g/mol}$

- So, we can now plug the numbers into the formula:

$$ n_{mol} = 5.72\ \mathrm{g} \cdot \frac{1\ \mathrm{mol}}{180.15588\ \mathrm{g/mol}} $$

-

So, the number of moles in 5.62 grams of glucose would be ~0.032 moles

-

Each mol contains $6.03 \cdot 10^{23}$ molecules, so $0.032$ moles would contain $1.93 \cdot 10^{22}$ molecules

-

We know that in one atom of glucose, there are 6 carbon atoms, 12 hydrogen atoms, and 6 oxygens, so that means there are 24 atoms in total

-

Therefore, because 5.72 grams of glucose is $1.93 \cdot 10^{22}$ molecules, and each molecules contains 24 atoms, the total number of atoms is $24 \cdot (1.93 \cdot 10^{22})$ which is $4.632 \cdot 10^{23}$

-

We can use the mole to convert into volume (for gases) as well, using this formula:

$$ n_{mol} \cdot 22.4\mathrm{L/mol} = n_l $$

- Essentially, the number of liters is equal to the number of moles multiplied by 22.4 liters/mol, which is based on the ideal gas formula

Stoichiometry in Chemical Reactions

- Suppose we are conducting a reaction that produces water from the combusion of hydrogen and oxygen gas, like this:

$$ \mathrm{2H_2} (g) + \mathrm{O_2}(g) \rightarrow \mathrm{2H_2O} (g) $$

-

You have 10 grams of hydrogen gas, and you want to find how many grams of water you can produce

-

To figure that out, you can use stoichiometry:

-

First, balance the equation (if it isn't balanced already)

-

Second, find out the ratios of the reactant to the product

-

There are 2 moles of our reactant, hydrogen, in $\mathrm{2H_2}$

-

There are 2 moles of our product, water, in $\mathrm{2H_2 O}$

-

-

That means the ratio is 2 moles to 2 moles or $2 \ratio 2$

-

Third, find the molar mass of your reactant

-

Our reactant is $\mathrm{H_2}$

-

Its total atomic mass in AMU is $2\cdot 1 = 2\ \mathrm{AMU}$

-

So its molar mass is $2\ \mathrm{g/mol}$

-

-

Forth, find the number of moles of your reactant

-

Use the formula $n_{mol} = M \cdot \frac{1\ \mathrm{mol}}{m_r}$

-

Here, $M$ is 10 grams, and $m_r$ is $2\ \mathrm{g/mol}$, so the number of moles is $10 \cdot \frac{1\ \mathrm{mol}}{2\ \mathrm{g/mol}}$ which is 5 moles

-

So we have 5 moles of hydrogen gas as the reactant

-

-

Fifth, use the ratio of reactant to product to find the number of moles of your product

- Use this formula:

-

$$ P_{mol} = n_{mol} \cdot \frac{P_m}{N_m} $$

-

This means that the number of moles of the product $P_{mol}$ is equal to the number of moles of the reactant $n_{mol}$ multiplied by the ratio of reactant to product $\frac{P_m}{N_m}$

-

For our equation, we already know that $n_{mol}$ is 5 moles

-

We also know that the ratio is $2 \ratio 2$

-

Putting these into the formula, that means the final formula is:

$$ P_{mol} = 5\ \mathrm{mol} \cdot \frac{2\ \mathrm{mol}\ \mathrm{H_2O}}{2\ \mathrm{mol}\ \mathrm{H_2}} $$

- After solving the equation, we find that $P_{mol}$ is 5 moles of water

-

-

Now, we need to convert moles back to grams

-

Recall that our formula for getting grams into moles is $n_{mol} = M \cdot \frac{1\ \mathrm{mol}}{m_r}$, and if we rearrange the formula, we also find that $M = n_{mol} \cdot \frac{m_r}{1\ \mathrm{mol}}$

-

We can simplify that into $M = n_{mol} \cdot m_r$

-

The molar mass ($m_r$) of water is approximately $18\ \mathrm{g/mol}$

-

We have 5 moles of water

-

So the total number of grams is $5 \cdot 18\ \mathrm{g/mol}$ which is 90 grams of water produced from 10 grams of hydrogen gas

-

But what if we're not trying to find the amount of product produced? What if we wanted to find how many grams of hydrogen ($\mathrm{H_2}$) will completely react with our 10 grams of oxygen gas? Here's how:

-

First, we have to establish the ratio between hydrogen and oxygen using the formula

-

We already have a balanced formula: $\mathrm{2H_2} (g) + \mathrm{O_2}(g) \rightarrow \mathrm{2H_2O} (g)$

-

From that, we know that hydrogen and oxygen are in a $2 \ratio 1$ ratio (we always list the unknown quantity first in a stoichiometric ratio, so don't mistakenly write 1:2!)

-

-

Second, we determine the number of moles of hydrogen from the given amount of oxygen

-

10 grams of oxygen is ~0.56 moles of oxygen, using the formula $n_{mol} = M \cdot \frac{1\ \mathrm{mol}}{m_r}$

-

Then, we find the number of moles of hydrogen corresponding to 0.56 moles of oxygen, using this formula:

$$ U_{mol} = N_{mol} \cdot \frac{U_m}{N_m} $$

-

-

Essentially, we find the number of moles of the unknown quantity ($U_{mol}$) from the known quantity ($N_m$) by multiplying the ratio between the two quantities

-

We know that the ratio is $2 \ratio 1$

-

So, our fomula is $0.56\ \mathrm{mol} \cdot \frac{2}{1} = 1.12\ \mathrm{mol}\ \mathrm{H_2}$

-

-

Last, we convert moles back to grams

-

1.12 moles of hydrogen gas, which has a molar mass of $2\ \mathrm{g/mol}$, is $1.12 \cdot 2 = 2.24\ \mathrm{g}$

-

Thus, we now know that 10 grams of oxygen will completely react with 2.24 grams of hydrogen!

-

Stoichiometry and Formula Units

Sometimes, you would be asked to give the number of formula units of a substance. That means you should provide the number of particles of the substance, based on its empirical formula. To do this, follow these steps:

-

Find the reaction's empirical formula

-

For instance, we will first balance the equation describing the combustion of glucose, which (in balanced form) is $\mathrm{C_6 H_{12} O_6} (s) + 6\mathrm{O_2}(g) \rightarrow 6\mathrm{CO_2} (g) + 6\mathrm{H_2 O} (g)$

-

Now, find the largest coefficient; here, our largest coefficient is 6

-

We divide everything now by 6, so now we have: $\frac{1}{6} \mathrm{C_6 H_12 O_6} (s) + 1\mathrm{O_2}(g) \rightarrow 1\mathrm{CO_2} (g) + 1\mathrm{H_2 O} (g)$

-

This is our empirical formula

-

-

Now, we can find the formula units of glucose

-

Glucose has a coefficient of $\dfrac{1}{6}$

-

The formula unit of glucose is its coefficient, multiplied by Avogadro's Number, which is $\frac{1}{6} \cdot 6.02 \times 10^{23}$

-

Solving that, we find that there are $\approx 1.003 \times 10^{23}$ units of glucose are formed; this is the formula unit of glucose

-

Common Stoichiometry Mistakes

Mistake 1

When converting between mass and moles, with this formula:

$$ n_{mol} = M \cdot \frac{1\ \mathrm{mol}}{m_r} $$

Remember that you always have 1 mole in the numerator! You cannot do this:

$$ n_{mol} \neq M \cdot \frac{20\ \mathrm{mol}}{m_r} $$

This would yield an incorrect number of moles!

Thermodynamics

Specific Heat Capacity

-

Enthalpy is a measure of the sum of all internal energy in a reaction

-

$Q$ is the the symbol for enthalpy in

-

We can calculate enthalpy with the specific heat formula $Q = mc\Delta t$

- $\Delta T$ is the final temperature, subtracted from the starting temperature, and can be negative

-

High specific heat means that an object will gain or lose energy very slowly, and is made of a material that is a thermal insulator

-

Low specific heat means that an object will gain or lose energy very quickly, and is made of a material that is a thermal conductor

Heating and Cooling Curves

-

Changes of state are fundamentally rrelated by energy changes in matter, which can be shown as substances undergo phrase transitions at their melting and boiling points - in other words, a heating curve

-

Below is a graph of temperature versus heat as matter changes state

-

Note that a cooling curve is basically just the exact same graph flipped horizontally

- Each area of the heating curve (and cooling curve) has specific properties, as shown below:

| Solid | Solid + Liquid | Liquid | Liquid + Gas | Gas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What happens in this region? | Temperature increases as heat is absorbed | Temperature remains constant as heat is used in the phase change until all solid has melted into liquid | Temperature increases as heat is absorbed | Temperature remains constant as heat is used in the phase change until all liquid has boiled to gas | Temperature increases as heat is absorbed |

| What is the equation for the heat change? | Specific heat capacity of a solid - $Q = mc_{\mathrm{solid}}$ | Latent heat of fusion - $Q = mc\Delta t$ or more simply $Q = mc (t_2 - t_a)$ | Specific heat capacity of a liquid - $Q = mc_{\mathrm{liquid}}$ | Latent heat of vaporization - $\Delta H_{\mathrm{vap}} = \Delta U_{\mathrm{vap}} + p\Delta V$ | Specific heat capacity of a gas - $Q = mc_{\mathrm{gas}}$ |

Calculating Heat Changes

- The basic formula of finding heat changes in a reaction is:

$$ A_{E_{loss}} = B_{E_{gain}} $$

-

In other terms, when two substances are placed about one another, the loss of heat of one and the gain of heat of another is equal

-

Or, in equation terms, $m_1 \cdot c_1 \cdot (T_1-T) = m_2 \cdot c_2 \Delta(T_2+T)$

-

Here, $T$ is the final temperature, also known as the equilibrium temperature

Examples

-

How do we find the final temperature, when 60.0 gram of warm water at 60.0 C° is mixed with 40.0 grams of cold water at 10.0 C°

-

We can find $T$, the final temperature, like this:

$$ m_1 \cdot c_1 \Delta T = m_2 \cdot c_2 \Delta T $$

- We know that the specific heat $c$ of both quantities of water is the same, so we can omit it:

$$ m_1 \Delta T = m_2 \Delta T $$

- Because the final temperature $T$ is unknown, we have to

$$ (60\ \mathrm{g})(60^\circ -T) = (40g) (T-10^\circ) $$

$$ T = 40.0^\circ $$

-

So the final temperature would be 40 degrees

-

For example, suppose a question asked to to find the final temperature of a 50.0 gram piece of iron (specific heat = $0.45\ \mathrm{J/g\cdot C^\circ}$) that is heated to 100 C° in boiling water and then dropped into 80.0 grams of water at 20.0 C°

-

We would setup the equation in this way:

$$ (50\ \mathrm{g})(0.45)(100^\circ -T) = (80\ \mathrm{g})(4.18)(T-20^\circ) $$

Endothermic Reactions

-

A reaction is endothermic when energy is absorbed from the surroudings and used to initiate and maintain the reaction, generating a net loss of energy in the surroundings

-

In an endothermic reaction, products have more potential energy than reactants

-

$\Delta H$ is positive in an endothermic reaction

Exothermic Reactions

-

A reaction is exothermic when energy is taken from the reactants and released to the surroundings, generating a net increase of energy in the surroundings

-

In an exothermic reaction, reactants have more potential energy than products

-

$\Delta H$ is negative in an exothermic reaction

Thermochemistry Calculations

We often want to find the change in heat energy, $\Delta H$, within a reaction.

Calculating Bond Energy

Using Hess's Law of Summation

- Hess's Law of Summation states that changes in enthalpy in a reaction ($\Delta H$) are independent of the pathway taken by the reactants to form the products:

$$ \Delta H = \sum \Delta H_{{{\mathrm f}\ (reactants)}} $$

- This means that enthalpy changes are cumulative, and can be added after every reaction

Hess's Law Example

-

Suppose we want to find out the enthalpy change in the reaction $\mathrm{4NH_3} + \mathrm{3O_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{2N_2} + \mathrm{6H_2O}$

-

We don't know the bond energies of any of the reactants or the products

-

We do know, however, of the enthalpy changes in several other reactions:

$$ \begin{cases} ① \mathrm{N_2} + \mathrm{3H_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{2NH_3}, :\Delta H =-92\mathrm{kJ} \ ② \mathrm{H_2} + \frac{1}{2}\mathrm{O_2} \rightarrow, :\Delta H = +286\mathrm{kJ} \end{cases}

$$

-

With Hess's Law, we can solve for our enthalpy change, using the provided equation

-

The basic idea is to match the equations where we know the enthalpy, with the equation that we don't know

-

Let's start with our first equation

- Notice how the first equation has $\mathrm{N_2}$, and our original equation also has $\mathrm{2N_2}$:

$$ \begin{cases} ① \underline\mathrm{N_2} + \mathrm{3H_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{2NH_3} \ ② \mathrm{4NH_3} + \mathrm{3O_2} \rightarrow \underline\mathrm{2N_2} + \mathrm{6H_2O}\end{cases} $$

-

Unforunately, the two nitrogens are on different sides of the equation

-

We can deal with that by flipping equation 1 around

-

Every time we flip an equation, we are going to reverse the sign of its enthalpy

-

If the enthalpy was positive, we change it to negative, and vice-versa

-

So, our flipped equation 1 has an enthalpy of $+92\mathrm{kJ}$ rather than $-92\mathrm{kJ}$

-

$$ \begin{cases} ① \mathrm{2NH_3} \rightarrow \underline\mathrm{N_2} + \mathrm{3H_2}, : \Delta H = +92\mathrm{kJ}\ ② \mathrm{4NH_3} + \mathrm{3O_2} \rightarrow \underline\mathrm{2N_2} + \mathrm{6H_2O}\end{cases} $$

- Now that they are on the same side, we now need to make $\mathrm{N_2}$ into $\mathrm{2N_2}$ by multiplying equation 1 by 2:

$$ \begin{cases} ① \mathrm{2\times 2NH_3} \rightarrow \underline\mathrm{2\times N_2} + \mathrm{2 \times 3H_2}, : \Delta H = 2 \times +92\mathrm{kJ}\ ② \mathrm{4NH_3} + \mathrm{3O_2} \rightarrow \underline\mathrm{2N_2} + \mathrm{6H_2O}\end{cases} $$

$$ \begin{cases} ① \mathrm{4NH_3} \rightarrow \underline\mathrm{2N_2} + \mathrm{6H_2}, : \Delta H = +184\mathrm{kJ}\ ② \mathrm{4NH_3} + \mathrm{3O_2} \rightarrow \underline\mathrm{2N_2} + \mathrm{6H_2O}\end{cases} $$

-

As we did before, we'll multiply the enthalpy by 2 as well

-

So the final form of our first equation is $\mathrm{4NH_3} \rightarrow \mathrm{2N_2} + \mathrm{6H_2}, : \Delta H = +184\mathrm{kJ}$

-

We can move on to do our second equation

- Notice how the second equation has $\mathrm{H_2O}$, and our original equation has $6H_2O$

$$ \begin{cases} ① \underline\mathrm{H_2O} \rightarrow \mathrm{H_2} + \frac{1}{2}\mathrm{O_2} \ ② \mathrm{4NH_3} + \mathrm{3O_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{2N_2} + \underline\mathrm{6H_2O}\end{cases} $$

-

As with before, we have $\mathrm{H_2O}$ in both equations, just on different sides

-

We have to flip the equation and change its enthalpy sign, to this:

$$ \begin{cases} ① \mathrm{H_2} + \frac{1}{2}\mathrm{O_2} \rightarrow \underline\mathrm{H_2O}, :\Delta H = \underline{-286\mathrm{kJ}} \ ② \mathrm{4NH_3} + \mathrm{3O_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{2N_2} + \underline\mathrm{6H_2O}\end{cases} $$

- Then, to change $\mathrm{H_2O}$ to $\mathrm{6H_2O}$, we need to multiply by 6, like this:

$$ \begin{cases} ① \mathrm{6 \times H_2} + 6 \times \frac{1}{2}\mathrm{O_2} \rightarrow \underline\mathrm{6 \times H_2O}, :\Delta H = 6 \times -286\mathrm{kJ} \ ② \mathrm{4NH_3} + \mathrm{3O_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{2N_2} + \underline\mathrm{6H_2O}\end{cases} $$

$$ \begin{cases} ① \mathrm{6H_2} + 3\mathrm{O_2} \rightarrow \underline\mathrm{6H_2O}, :\Delta H = -1716\mathrm{kJ} \ ② \mathrm{4NH_3} + \mathrm{3O_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{2N_2} + \underline\mathrm{6H_2O}\end{cases} $$

-

So the final form of our second equation is $\mathrm{4NH_3} + \mathrm{3O_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{2N_2} + \mathrm{6H_2O}$

-

Lastly, we add equations ① and ② together

$$ \begin{array}{lcl} &\mathrm{4NH_3} \rightarrow \mathrm{2N_2} + \mathrm{6H_2}, : \Delta H = +184\mathrm{kJ} \

- : &\mathrm{6H_2} + 3\mathrm{O_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{6H_2O}, :\Delta H = -1716\mathrm{kJ} \end{array} $$

- And this is the result (we cancel out terms that appear both in the products and the reactants):

$$ \mathrm{4NH_3} + \cancel\mathrm{6H_2} + \mathrm{3O_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{2N_2} + \cancel\mathrm{6H_2}+\mathrm{6H_2O, :\Delta H = }-1532\mathrm{kJ} $$

$$ \mathrm{4NH_3} + \mathrm{3O_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{2N_2} + \mathrm{6H_2O, :\Delta H = }-1532\mathrm{kJ} $$

Gibbs Free Energy

- Gibbs free energy (often represented by $\Delta G$) tells us whether a reaction is spontaneous or non-spontaneous

- Spontaneous reactions happen because the reactants have enough activation energy to form the activation complex, but they don't necessarily have to go fast

- Non-spontaneous reactions don't have enough activation energy - they won't react until we do something to it

- Entropy is the tendency of a thermodynamic system, such as a chemical reaction, to shift toward a state of disorder

- Solids have the least amount of entropy; gases have the greatest amount of entropy

- Entropy is represented by $\Delta S$

- Temperature in thermodynamics is given in Kelvin units, and is represented by $T$

- The Gibbs free energy equation relates enthalpy, entropy, and Gibbs free energy, with the following formula:

$$ \Delta G = \Delta H - T(\Delta S) $$

- If $\Delta G$ is negative, the reaction is spontaneous

- If $\Delta G$ is positive, the reaction is non-spontaneous

- If $\Delta G$ is 0, the reaction is at equilibrium

Solutions

-

When we have a mixtures where one substance is dissolved in another substance, we call it a solution

-

The solute is the dissolved substance, and is also the part of the solution in lesser quantity

- Some common solutes include salt (sodium chloride) and sugar (glucose)

-

The solvent is the substance that dissolves the solute, and is also the part of the solution in greater volume

-

A certain amount of a solvent can only dissolve a certain quantity of solute

-

A solvent is considered saturated if it can dissolve no more solute

-

To make a solvent dissolve more solute, we could do the following:

-

Add heat energy (which is why solids dissolve more quickly in hot water than cold water)

- Note that gases typically dissolve more quickly in cold solutions than hot solutions

- That is what allows fish to breath (from oxygen dissolved in water) even while the water surface is frozen in wintertime

-

Increase the surface area by crushing up the solute

-

Agitate the solution (stirring)

-

-

The concentration of a solution is the qualit

-

There are numerous ways to measure the concentration of a solution

-

Percent by mass: the mass of the solute, divided by the mass of the solution

-

Percent by volume: the volume of the solute, divided by the volume of the solution

-

Molarity (represented by $M$): the moles of solute, divided by liters of solution, and the preferred unit in chemistry

Calculating molarity of a solution

The general formula for the molarity of a solution is:

$$ M = \frac{M_s}{V_s} $$

-

$M$, as we know, is the molarity of a solution, measured in the unit $M$

-

$M_s$ is the molar mass of the solute, measured in moles

-

$V_s$ is the total volume of the solution, measured in liters

Solution molarity question examples

-

You might encounter a question like this: Determine the molarity of a solution made by dissolving 33.0 grams of $\mathrm{CaCl_2}$ in enough water to make 600.0 ml of solution.

-

To solve this question, we need to find the molar mass of the solute and the solution volume

-

While we don't know the molar mass $(M_s)$, we do know that the solute is calcium chloride, and that its mass is 33 grams

-

We know that we can convert grams to moles with the formula $n_{mol} = M \cdot \frac{1\ \mathrm{mol}}{m_r}$

-

The molar mass of calcium chloride can be calculated from its atomic mass, which would be 110 g/mol

-

So 33 grams is equal to $33 \cdot \frac{1\ \mathrm{mol}}{100\ \mathrm{g/mol}}$, which is 0.3 mol

-

Therefore, $M_s$ is equal to 0.3 mol

-

-

We are told that there are 600 ml of total solution

-

The total volume of the solution $V_s$ needs to be in liters though, and 600 ml is 0.6 liters

-

So $V_s$ is equal to 0.6 L

-

-

Now, we just need to plug our values of $M_s$ and $V_s$ into the equation

-

$M = \frac{M_s}{V_s}=\frac{0.3\ \mathrm{mol}}{0.6\ \mathrm{L}}$

-

Therefore, $M = 0.5\ \mathrm{M}$

-

-

Our solution has a molarity of 0.5 M

-

Determining Percent Mass

-

Percent mass is the percentage of a solute's mass in a solution's total mass

-

If we had 1 gram of salt dissolved in 100 grams of solution, for example, then we would say that salt made up 1% of the solution's mass

-

So the percent mass of salt would be 1%

-

However, what if we had 1 gram of salt, dissolved in 49 grams of water?

-

We don't know the total mass of the solution

-

But since we know that the total mass of the solution is equal to the mass of the solute plus the mass of the solvent, or 1 gram of salt plus 49 grams of water, we can deduce that the total mass would be 50 grams

-

-

So, a general equation of percent mass is this:

Determining Mole Fraction

-

The mole fraction is the number of moles of a solute, divided by the total moles of all of the solute and solvent

-

Remember, its units are in moles - not mass units!

-

The formula for finding mole fraction, assuming you only have one solute, is:

$$ M_f = \frac{M_s}{M_s + M_v} $$

-

In this equation:

-

$M_f$ is the mole fraction

-

$M_s$ is the moles of solute

-

$M_v$ is the moles of solvent

-

-

For instance, you might be asked to find the mole fraction of glucose, $\mathrm{C_6 H_{12} O_6}$, if 36 grams of glucose were dissolved in 90 grams of water

-

You've already determined that the molar mass of glucose is 180 g/mol, and the molar mass of water is 18 g/mol

-

Using the formula $n_{mol} = M \cdot \frac{1\ \mathrm{mol}}{m_r}$, we find that there are 0.2 moles of glucose, and 5.0 moles of water

-

Last, using the mole fraction formula, $M_f = \frac{0.2}{(5.0 + 0.2)}$, which gives us a final mole fraction of $\frac{1}{26}$ or around 0.0385

-

Boiling Point Elevations

-

As more solute is added to a solvent, the boiling point of a solvent increases

-

For instance, chefs often add salt when cooking noodles in boiling water

-

The salt increases the boiling point of water

-

This means the water has to be at a higher temperature in order to boil

-

So chefs can cook noodles in water even at temperatures above boiling point, allowing them to cook the noodles faster

-

Calculating Boiling Point Elevations

- Boiling point elevation is calculated with this equation:

$$ N_b = O_b + (k \cdot M) $$

-

In this equation:

-

$N_b$ is the boiling point of the solution (aka solvent with solute)

-

$O_b$ is the boiling point of the pure solvent

-

$k$ is the boiling point elevation constant (which is the same as the freezing point depression constant), usually provided for you

-

$M$ is the molar concentration of the solution

-

-

For instance, we might be asked to find the boiling point of a 2M solution of calcium chloride within water, and that $k = 1.86$

-

We know that the solvent is water, which has a pure boiling point ($O_b$) of 100 degrees Celcius

-

We also know that the molar concentration is 2M

-

Thus, with our equation, $N_b = 100^\circ + (1.86 \cdot 2\mathrm{M})$ which gives a final boiling point of 103.72 degrees Celcius

-

Freezing Point Depressions

-

As more solute is added to a solvent, the freezing point of a solvent decreases

-

For instance, putting salt on winter roads decreases the freezing point of water

-

That means water needs to be at a colder temperature in order to freeze

-

So it prevents roads from freezing over with ice

-

Calculating Freezing Point Depressions

- Freezing point depression is calculated with the following equation:

$$ N_f = O_f - (k \cdot M) $$

-

In this equation:

-

$N_f$ is the freezing point of the solution (aka solvent with solute)

-

$O_f$ is the freezing point of the pure solvent

-

$k$ is the freezing point depression constant (which is the same as the boiling point elevation constant), usually provided for you

-

$M$ is the molar concentration of the solution

-

-

For instance, we might be asked to find the molar mass of an unknown solute if 20.0 grams of it dissolved in 100.0 grams of water lowers the freezing point to -1.45° Celcius, assuming $k = 1.86$

-

Note that in this question, we don't know the molar concentration ($M$), so we have to figure out that first

-

We know that the freezing point ($N_f$) of the solution is -1.45° Celcius, and that the normal freezing point of pure water ($O_f$) is 0° Celcius

-

Because $N_f = O_f - (k \cdot M)$, we could rearrange the equation to find that $O_f - N_f = (k \cdot M)$, and so $0 - (-1.45) = 1.45 = (k \cdot M)$

-

We also know that $k = 1.86$, so $1.45 = (1.86 \cdot M)$

-

Thus, $\frac{1.45}{1.86} = M$, and $M \approx 0.780$

-

Remember the equation for molar concentration? It is $M = \frac{M_s}{V_s}$

-

That means $0.780 = \frac{M_s}{V_s}$

-

And while we don't know molar mass, we can find solvent volume ($V_s$)

-

As we are told the we have 100 grams of water, we know that 100 grams is equal to 100 ml (which is also equal to 0.1 liters)

-

So that means $V_s = 0.1\ \mathrm{L}$

-

Now, substituting those two values, we find that $0.780 = \frac{M_s}{0.1\ \mathrm{L}}$

-

Rearranging that equation gives us $M_s = 0.780 \cdot 0.1\ \mathrm{L} = 0.078\ \mathrm{mol}$

-

-

We've got our final answer - the molar mass of the solute is 0.078 mol

-

Gas Laws

- When studying gases, there are 3 laws that we use all the time:

- Boyle's law, which relates pressure and volume

- Charles's law, which relates temperature and volume

- And Gay-Lussac's law, which relates pressure and temperature

Boyle's Law

- Boyle's law states that a change in pressure is inversely proportional to the change in volume

- It is often represented by this equation:

$$ P \propto \frac{1}{V} $$

- Here, $P$ represents pressure, $V$ represents volume, and the $\propto$ sign means that pressure is proportional to the inverse of the volume (which is why it's $\frac{1}{V}$)

- The version of Boyle's law that we commonly use for solving equations, however, is a derived form of the previous equation, and it is this:

$$ P = \frac{k}{V} $$

- Here, we have a equation of direct equivalence (that means it's got an equal sign) where the constant of proportionality $k$ is equal to $P \cdot V$

- In simpler terms, we always divide the same number $k$ by $V$ to get $P$

Charles's Law

- Charles's law states that a change in temperature is directly proportional to the change in volume

- It is often represented by this equation:

$$ T \propto V $$

- Here, $T$ is the temperature, and $V$ is the volume

- We can also rewrite this equation like this:

- $T = k \cdot V$, where the equation is one of direct equivalence again where the constant $k$ remains the same for any temperature and any volume

Gay-Lussac's Law

- Gay-Lussac's law states that when the volume is held constant, the ratio of the pressure to the temperature is also constant, so a change in pressure will cause a directly proportional change in temperature

- Its equation is this:

$$ \frac{P}{T} = k $$

The Combined Gas Law

- If we join the equations for the three gas laws together, we get the combined gas law:

$$ \frac{P \cdot V}{T} = k $$